Coming Home to Orna Villa

by Lisa Dorward

How did a girl from Ohio, who was raised in California, come “home” to a grand old plantation house in Georgia? The question is asked of me a lot. Well, it’s really a love story – about how I fell in love with Orna Villa and a little college town called Oxford.

I love old houses. Ever since I was a little girl, I dreamed of living in and restoring a grand old house. This yearning in me went long unsatisfied because I lived nearly all of my life in southern California, an area where a "historic" building rarely dates back before the 1920’s.

Our family moved to California from Ohio when I was only six years old, but for some reason, I never thought of California as “home.” Nevertheless, I stayed in California, where I graduated from college, raised a family as a young single mother and, like far too many of us, spent many years in a career that I did not like. When my children had grown and were (pretty much) on their own, I decided to reclaim and reinvent myself. I love history and had always wanted to be a writer of historical fiction. I had a B.A. in history, so I went back to college for another B.A., this time in English, then on to graduate school for an MFA in writing. I had gone to a writer’s conference and attended a seminar taught by professor and author, Gail Adams. That evening, I read her book, Purchase of Order, and knew with all the certainty of an epiphany that I had found my mentor. I had to – simply had to -- study writing under her. She taught at West Virginia University and, as fate would allow, I was accepted into their MFA program.

So, I packed up everything and moved to Morgantown, West Virginia. I bought a charming home in the historic district, just a few blocks from campus. It was in need of some renovations, which I lovingly undertook during school breaks because, as I said, I love old houses. It was lovely, but I knew it was not my forever home. I had a very clear image of the home I wanted -- quite literally my "dream house," for I had been having a recurring dream of what I called my “happily-ever-after home” for many years. I knew everything about it, from the curve of the driveway to the chandelier in the dining room, to the staircase, to the long front yard ... and most importantly, the feeling of home it gave me.

I finished my MFA and, after being sidelined by fate for a while, began my quest for my own holy grail: home. I saw pictures of Orna Villa while house-hunting on the internet but the pictures didn't do it justice and I wasn't at all sure it was the house for me. In fact, I had made a list of twelve houses I wanted to see all around the state of Georgia (not to mention the houses I had looked at in half a dozen other states!). I flew down to Georgia with my list (and map) in hand.

The moment I saw Orna Villa, I knew. I knew as soon as I turned into the long driveway ... that familiar curve around ancient trees, the long yard stretching up to the house sitting far back from the street. I could tell in an instant that the house had been vacant for a long time – not because it was in poor condition -- on the contrary, it was ever so lovely -- but because no empty house can ever seem to disguise its loneliness. I stopped my car at the top of the driveway and got out to look at the house from a distance and stood in what I can only describe as a moment of mutual recognition followed by a wave of relief, belonging, and joy. It was as though the house had been waiting for me and now was welcoming me back after a long, long time away -- welcoming me home.

Ever since I moved to Orna Villa, every week, without fail, another stranger comes to my door, and tells me that his grandmother had been married here, or her great-grandfather was born here, or his great-great grandmother loved to talk about how she played here as a child. I welcome them into my home, recognizing that Orna Villa can never really belong to only me -- or to any one person. We who buy these lovely old houses are caretakers, not only of history, but of heritage.

“If walls could talk …” they say -- but walls do talk, I say – and anyone who lives in a historic home will say the same. And this peculiar breed of homeowner will also tell you that it is impossible to live in a historic house without listening to its stories. It's part of the peculiar make-up of the kind of person who takes on all the perils and pitfalls of maintaining (let alone restoring) an old house to want to hear those stories and become part of them -- but there's much more to it than that.

Most of us feel a deep responsibility to the community. Every historic home is a living member of its community and by signing the deed, we are also signing a covenant with that community as well as with the house itself -- to tell its stories and keep it alive. Like people, houses are alive as long as they are cherished -- as long as their stories are told.

I love old houses. Ever since I was a little girl, I dreamed of living in and restoring a grand old house. This yearning in me went long unsatisfied because I lived nearly all of my life in southern California, an area where a "historic" building rarely dates back before the 1920’s.

Our family moved to California from Ohio when I was only six years old, but for some reason, I never thought of California as “home.” Nevertheless, I stayed in California, where I graduated from college, raised a family as a young single mother and, like far too many of us, spent many years in a career that I did not like. When my children had grown and were (pretty much) on their own, I decided to reclaim and reinvent myself. I love history and had always wanted to be a writer of historical fiction. I had a B.A. in history, so I went back to college for another B.A., this time in English, then on to graduate school for an MFA in writing. I had gone to a writer’s conference and attended a seminar taught by professor and author, Gail Adams. That evening, I read her book, Purchase of Order, and knew with all the certainty of an epiphany that I had found my mentor. I had to – simply had to -- study writing under her. She taught at West Virginia University and, as fate would allow, I was accepted into their MFA program.

So, I packed up everything and moved to Morgantown, West Virginia. I bought a charming home in the historic district, just a few blocks from campus. It was in need of some renovations, which I lovingly undertook during school breaks because, as I said, I love old houses. It was lovely, but I knew it was not my forever home. I had a very clear image of the home I wanted -- quite literally my "dream house," for I had been having a recurring dream of what I called my “happily-ever-after home” for many years. I knew everything about it, from the curve of the driveway to the chandelier in the dining room, to the staircase, to the long front yard ... and most importantly, the feeling of home it gave me.

I finished my MFA and, after being sidelined by fate for a while, began my quest for my own holy grail: home. I saw pictures of Orna Villa while house-hunting on the internet but the pictures didn't do it justice and I wasn't at all sure it was the house for me. In fact, I had made a list of twelve houses I wanted to see all around the state of Georgia (not to mention the houses I had looked at in half a dozen other states!). I flew down to Georgia with my list (and map) in hand.

The moment I saw Orna Villa, I knew. I knew as soon as I turned into the long driveway ... that familiar curve around ancient trees, the long yard stretching up to the house sitting far back from the street. I could tell in an instant that the house had been vacant for a long time – not because it was in poor condition -- on the contrary, it was ever so lovely -- but because no empty house can ever seem to disguise its loneliness. I stopped my car at the top of the driveway and got out to look at the house from a distance and stood in what I can only describe as a moment of mutual recognition followed by a wave of relief, belonging, and joy. It was as though the house had been waiting for me and now was welcoming me back after a long, long time away -- welcoming me home.

Ever since I moved to Orna Villa, every week, without fail, another stranger comes to my door, and tells me that his grandmother had been married here, or her great-grandfather was born here, or his great-great grandmother loved to talk about how she played here as a child. I welcome them into my home, recognizing that Orna Villa can never really belong to only me -- or to any one person. We who buy these lovely old houses are caretakers, not only of history, but of heritage.

“If walls could talk …” they say -- but walls do talk, I say – and anyone who lives in a historic home will say the same. And this peculiar breed of homeowner will also tell you that it is impossible to live in a historic house without listening to its stories. It's part of the peculiar make-up of the kind of person who takes on all the perils and pitfalls of maintaining (let alone restoring) an old house to want to hear those stories and become part of them -- but there's much more to it than that.

Most of us feel a deep responsibility to the community. Every historic home is a living member of its community and by signing the deed, we are also signing a covenant with that community as well as with the house itself -- to tell its stories and keep it alive. Like people, houses are alive as long as they are cherished -- as long as their stories are told.

The Story of Orna Villa and Dr. Alexander Means

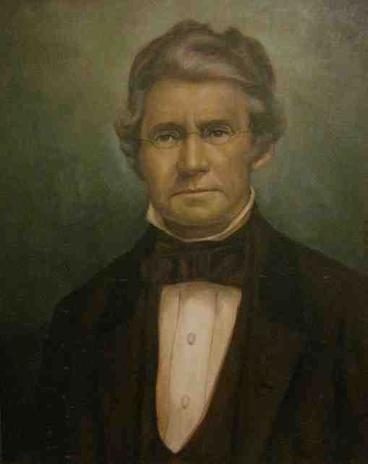

This portrait of Alexander Means still hangs over the mantle in the dining room at Orna Villa, passed from each loving resident of the great house to the next.

After a brief stint as a teacher and then a store clerk, Alexander Means moved to what was then the very rural frontier of Georgia where he studied medicine under the guidance of a Dr. Randolf and a Dr. Walker. There was little in the way of formal medical schools in the early 1800s; in fact, even well into the twentieth century, 90 percent of all doctors had no college education at all, but learned their profession through tutelages and apprenticeships under practicing doctors. However, Dr. Means did attend one session at Transylvania College's School of Medicine in Lexington Kentucky in 1825. He then returned to Georgia and formed a medical practice with Dr. Henry Gaither in Covington.

After a brief stint as a teacher and then a store clerk, Alexander Means moved to what was then the very rural frontier of Georgia where he studied medicine under the guidance of a Dr. Randolf and a Dr. Walker. There was little in the way of formal medical schools in the early 1800s; in fact, even well into the twentieth century, 90 percent of all doctors had no college education at all, but learned their profession through tutelages and apprenticeships under practicing doctors. However, Dr. Means did attend one session at Transylvania College's School of Medicine in Lexington Kentucky in 1825. He then returned to Georgia and formed a medical practice with Dr. Henry Gaither in Covington.

A Virginian by the name of Richard Keenon Dearing had come to Georgia in 1793 and purchased 2,000 acres of land on which he built a four-room plantation house of hand-hewn logs. Dr. Means bought the house from Dearing around 1820 and set about expanding and remodeling it into the grand Greek Revival house it is today. Among Dr. Means’s many interests was ornithology, so he named his home that stood among the trees, Orna Villa, meaning “Bird House.”

Here is a picture of Dr. Means's "medical bag." While to a modern eye, it may look more like a carpenter's tool box, this is typical of the medical instrumentation of the time. It was found and continues to be lovingly preserved by Jim Watterson, who was the thirteenth owner of Orna Villa and who, still living in Oxford, is now a dear, dear friend of mine.

Here is a picture of Dr. Means's "medical bag." While to a modern eye, it may look more like a carpenter's tool box, this is typical of the medical instrumentation of the time. It was found and continues to be lovingly preserved by Jim Watterson, who was the thirteenth owner of Orna Villa and who, still living in Oxford, is now a dear, dear friend of mine.

The Gift of a Bell

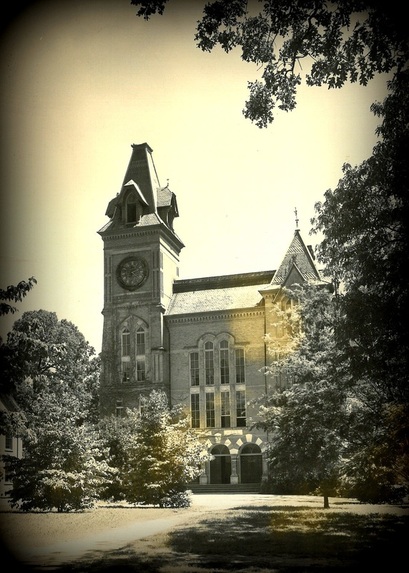

Just a couple blocks from Orna Villa is Emory University's Oxford College. The campus was the original site of the university (even before it was a “university”) and remained within the university system when the main campus was relocated to Atlanta after the Civil War (but that’s another story).

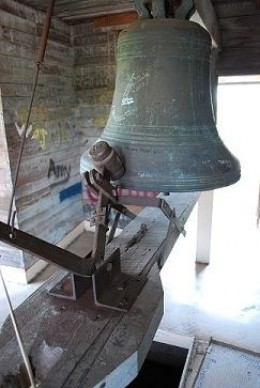

The Oxford campus is steeped in history, weathering the storms of the Civil War, Reconstruction, two world wars, segregation, social upheaval, and technological advancements that defy the imagination, all while still retaining its original elegance. Every half-hour a bell tolls from Seney Hall at Oxford College. It is a matter of great tradition ... and, like most things in Oxford, just a little controversy.

The bell was donated to the college by Alexander Means in 1855. It was first housed in the Administration Building until that building burned down in 1872. It then hung from a tree in the Quadrangle in the center of the campus until the clock tower of Seney Hall was completed in 1881, which is where it remains to this day. It should not be surprising, though, that the community-minded custodians of history who make up this charming town have preserved the tree limb that supported the bell in the Quadrangle to keep the story alive for future generations.

The Oxford campus is steeped in history, weathering the storms of the Civil War, Reconstruction, two world wars, segregation, social upheaval, and technological advancements that defy the imagination, all while still retaining its original elegance. Every half-hour a bell tolls from Seney Hall at Oxford College. It is a matter of great tradition ... and, like most things in Oxford, just a little controversy.

The bell was donated to the college by Alexander Means in 1855. It was first housed in the Administration Building until that building burned down in 1872. It then hung from a tree in the Quadrangle in the center of the campus until the clock tower of Seney Hall was completed in 1881, which is where it remains to this day. It should not be surprising, though, that the community-minded custodians of history who make up this charming town have preserved the tree limb that supported the bell in the Quadrangle to keep the story alive for future generations.

Dr. Means's bell has marked more than the passage of time, however. On a cold day in January, 1866, it rang out to signal the reopening of the college after it had been closed for the duration of the Civil War, when the college served as a barracks and hospital. And at every annual commencement, the bell tolls once in honor of each student graduating that year.

How Dr. Means came to give the bell to the college is, like many Orna Villa legends, shrouded in mystery. There are two competing stories.

In 1931, the Emory Alumnus magazine published an appeal for anyone with knowledge of how the bell came to Oxford. They received two letters. The first was from George W.W. Stone (class of 1875) who wrote, "When Napoleon overran Spain he seized a great number of convent bells and sent them into Paris to be molded into cannons. . . . Dr. Alexander Means went to Europe [in the mid-1850s], and while in Paris, he bought this bell."

After reading Stone's letter, Dr. Sara E. Branham, a renowned Washington, D.C., bacteriologist who was born and raised in Oxford, wrote to take issue with the account. "We literally grew up with that bell," she wrote, "and as children we of Oxford were told only one story. . . . Doctor Means and Queen Victoria were good friends, and she was so interested in the fact that Emory was in a town named Oxford after the English university town, that she wished to express her interest by presenting a bell for the college clock."

How Dr. Means came to give the bell to the college is, like many Orna Villa legends, shrouded in mystery. There are two competing stories.

In 1931, the Emory Alumnus magazine published an appeal for anyone with knowledge of how the bell came to Oxford. They received two letters. The first was from George W.W. Stone (class of 1875) who wrote, "When Napoleon overran Spain he seized a great number of convent bells and sent them into Paris to be molded into cannons. . . . Dr. Alexander Means went to Europe [in the mid-1850s], and while in Paris, he bought this bell."

After reading Stone's letter, Dr. Sara E. Branham, a renowned Washington, D.C., bacteriologist who was born and raised in Oxford, wrote to take issue with the account. "We literally grew up with that bell," she wrote, "and as children we of Oxford were told only one story. . . . Doctor Means and Queen Victoria were good friends, and she was so interested in the fact that Emory was in a town named Oxford after the English university town, that she wished to express her interest by presenting a bell for the college clock."

Dr. Branham's account was latter corroborated by Dr. Means' granddaughter, Sue Means Johnson and for many years was accepted as definitive. A number of articles over the years have reported that Dr. Means visited Europe in the mid-1850s and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society by Queen Victoria, which seemed to further substantiate the account.

Then in 1975, Jane J. King (now Walsh), who earned her degree from Oxford in 1977, wrote to The Royal Society asking for information about the bell and Dr. Means. The Royal Society librarian N. H. Robinson responded to her inquiry, writing "I can only inform you that [Means] was not a Fellow of the Royal Society and we do not have any information about him. I cannot find his name mentioned in any of the standard biographies and I have been unable to trace any original correspondence. I am also not familiar with the story that Dr. Means was presented with a large bell by Queen Victoria."

While this does not definitively dispel the legend of the Queen and Dr. Means, it does keep the mystery alive.

Then in 1975, Jane J. King (now Walsh), who earned her degree from Oxford in 1977, wrote to The Royal Society asking for information about the bell and Dr. Means. The Royal Society librarian N. H. Robinson responded to her inquiry, writing "I can only inform you that [Means] was not a Fellow of the Royal Society and we do not have any information about him. I cannot find his name mentioned in any of the standard biographies and I have been unable to trace any original correspondence. I am also not familiar with the story that Dr. Means was presented with a large bell by Queen Victoria."

While this does not definitively dispel the legend of the Queen and Dr. Means, it does keep the mystery alive.

Slavery at Orna Villa

The record shows that Orna Villa had, at any given time prior to emancipation, between 20 to 28 slaves. Records are incomplete and tracing details of the lives of the African-Americans living in slavery are difficult to come by. Dr Gary Hauk, vice president and deputy to the president at Oxford College of Emory University, authored a book entitled, A Legacy of Heart and Mind about the history of Emory University and its beginnings at Oxford. He and Dr. Sally Wolff King co-edited a volume of historical accounts that chronicle the stories of slavery in Oxford entitled, Where Courageous Inquiry Leads: The Emerging Life of Emory University. Their research has brought to light a few stories pertinent to Orna Villa and what life was like there prior to emancipation.

Of the slaves who lived at Orna Villa, the following names are known:

Albert (b. 1818)

Fanny (b. 1828)

Harriet (1852 - 1861)

Iveson (b. 1858)

Thaddius

Anna Tinsley

However, there are a few others for whom more than just their identities are known:

Samuel Means (b. 1806) was an accomplished blacksmith and carpenter. He was married to Louisa (b.1832), who was enslaved by George W. W. Stone Sr., professor of mathematics at Emory University, for whom she worked her entire life, even after emancipation. Samuel was "rented out" by Dr. Means to a man in West Point, Georgia for $300 per year. There was a provision made in the contract that Sam would be allowed 4 visits home per year to see his wife and family.

Of the slaves who lived at Orna Villa, the following names are known:

Albert (b. 1818)

Fanny (b. 1828)

Harriet (1852 - 1861)

Iveson (b. 1858)

Thaddius

Anna Tinsley

However, there are a few others for whom more than just their identities are known:

Samuel Means (b. 1806) was an accomplished blacksmith and carpenter. He was married to Louisa (b.1832), who was enslaved by George W. W. Stone Sr., professor of mathematics at Emory University, for whom she worked her entire life, even after emancipation. Samuel was "rented out" by Dr. Means to a man in West Point, Georgia for $300 per year. There was a provision made in the contract that Sam would be allowed 4 visits home per year to see his wife and family.

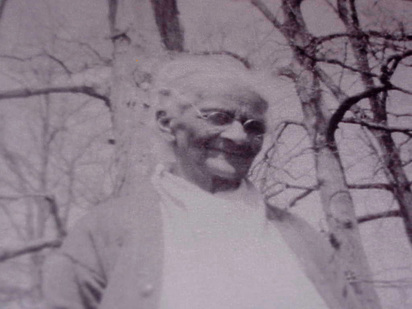

Cornelius Robertson (b. 1836) was a Native American and served as Dr. Means's valet. He was married to Ellen Robertson (b. 1835), an African American. They lived in a small, one-room house behind Orna Villa (pictured here), which is still standing. Ellen was a lady’s maid to Mrs. Means. After emancipation, Cornelius and Ellen formed an independent household and the census of 1870 shows that they had 5 children: Cora (b. 1857),

Sarah Robinson

Sarah Robinson

George (b.1859), Sarah (b.1861), John (b. 1863) and Thadius (b. 1867). Cornelius and Ellen’s daughter Sarah Robinson married Robert Mitchell (son of Thomas Mitchell, who was enslaved by Bishop Andrew). One of their sons, Henry "Billy" Mitchell, worked as a custodian at Emory College for much of the first half of the 20th century.

Henry Robinson (b.1806) was sent off to war as the servant to Dr. Means's son, Thomas Alexander Means, who was in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Henry returned to Oxford in November of 1861 after serving in the First Battle of Manassas to find that Dr. Means had sold him, his wife Milly (b. 1811) and their 3 children, Mildred (b. 1836), Thomas (b. 1850), and Troup (b. 1852) to Judge Reynolds in Covington. Henry and his family were terribly distraught. Dr. Means recorded in his diary: "Henry is much distressed and unwilling to go." Apparently, Henry and Milly's adult daughter, Mildred, was particularly upset. Dr. Means wrote that "Milly's insolence and angry retorts first induced me to think of parting with them." But Means finally relented and convinced Judge Reynolds to release him from the contract. However, Dr. Means was so angry at Mildred, he insisted on selling her along with her young child, writing, "Mildred [is] much in fault and therefore I sell Mildred who expressed a desire that I should [do] so." Records indicate that the entire family was reunited after the Civil War, however, there is no mention of Mildred's young child. It is unknown what happened to him (her?).

Henry Robinson (b.1806) was sent off to war as the servant to Dr. Means's son, Thomas Alexander Means, who was in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Henry returned to Oxford in November of 1861 after serving in the First Battle of Manassas to find that Dr. Means had sold him, his wife Milly (b. 1811) and their 3 children, Mildred (b. 1836), Thomas (b. 1850), and Troup (b. 1852) to Judge Reynolds in Covington. Henry and his family were terribly distraught. Dr. Means recorded in his diary: "Henry is much distressed and unwilling to go." Apparently, Henry and Milly's adult daughter, Mildred, was particularly upset. Dr. Means wrote that "Milly's insolence and angry retorts first induced me to think of parting with them." But Means finally relented and convinced Judge Reynolds to release him from the contract. However, Dr. Means was so angry at Mildred, he insisted on selling her along with her young child, writing, "Mildred [is] much in fault and therefore I sell Mildred who expressed a desire that I should [do] so." Records indicate that the entire family was reunited after the Civil War, however, there is no mention of Mildred's young child. It is unknown what happened to him (her?).

The Civil War Era - Orna Villa's role in the historic conflict

While originally against secession, Alexander Means became caught up in the turbulent times leading up to the Civil War. In 1861, he became a member of the Georgia Secession Convention and spoke passionately against secession. When the first test vote was taken, Dr. Means and 129 other delegates voted against secession while 165 delegates voted for it. Another test vote was taken yielding nearly the same result. Since it was evident that the secessionist would carry the day, Means cast his vote with the majority when the official vote was taken because he felt it was important to "present as solid a front as possible to our enemies by swelling the majority vote."

The writings in his diary reveal that Dr. Means was devoted to the Confederacy. He delivered an impassioned speech at the Covington Courthouse on January 21, 1862 calling for volunteers for the Confederate Army. "Old men wept and young men shouted and shed tears ... and volunteers came forward."

In those days, there was an old walnut tree grove on the Orna Villa property. In November of 1864, the famed Confederate spy, Zora Fair used the juice from Orna Villa's walnuts to stain her face so that she could pass for a mulatto, slip through Yankee lines and into General Sherman's camp where she overheard plans for his famous "March to the Sea." There are conflicting historical accounts as to whether she passed her information on to Confederate General Johnston and he ignored it, or that she (or a letter from her) was intercepted before she could report what she heard. In either case, the intelligence she gathered did not reach anyone who could change the course of events. After the war, Zora returned to North Carolina and is said to have died of a broken heart within two months after the South was defeated.

In the banister of the staircase of Orna Villa there is a sizeable gash in the wood. Legend has it that this was caused by a bullet fired at Toby Means by one of General Sherman's approaching soldiers through the open front door, as Toby was escaping out the back door. However, other accounts have said that it was Dr. Means’s previously wounded and recuperating son-in-law who escaped through a window in the back of the house when he heard that Union troops were coming through Oxford, and that no shot was fired.

The writings in his diary reveal that Dr. Means was devoted to the Confederacy. He delivered an impassioned speech at the Covington Courthouse on January 21, 1862 calling for volunteers for the Confederate Army. "Old men wept and young men shouted and shed tears ... and volunteers came forward."

In those days, there was an old walnut tree grove on the Orna Villa property. In November of 1864, the famed Confederate spy, Zora Fair used the juice from Orna Villa's walnuts to stain her face so that she could pass for a mulatto, slip through Yankee lines and into General Sherman's camp where she overheard plans for his famous "March to the Sea." There are conflicting historical accounts as to whether she passed her information on to Confederate General Johnston and he ignored it, or that she (or a letter from her) was intercepted before she could report what she heard. In either case, the intelligence she gathered did not reach anyone who could change the course of events. After the war, Zora returned to North Carolina and is said to have died of a broken heart within two months after the South was defeated.

In the banister of the staircase of Orna Villa there is a sizeable gash in the wood. Legend has it that this was caused by a bullet fired at Toby Means by one of General Sherman's approaching soldiers through the open front door, as Toby was escaping out the back door. However, other accounts have said that it was Dr. Means’s previously wounded and recuperating son-in-law who escaped through a window in the back of the house when he heard that Union troops were coming through Oxford, and that no shot was fired.

Alexander Means: Renaissance Man

The life of Alexander Means intersected with some very well-known figures in history. He entertained President Millard Fillmore at Orna Villa, was received by Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales in London, was a house guest of Sir Michael Faraday and Charles Lyell, and he delivered the funeral oration for President Zachary Taylor in 1850.

Dr. Means became a Methodist minister in 1828 and was described as a "preacher of rare eloquence." He received speaking invitations from Dr. Wilbur Fisk, the president of Connecticut University, and President Zachary Taylor. Many of his sermons, speeches, reviews and scientific discussions were published and widely circulated.

The Methodist/Episcopal Georgia Conference formed a "manual labor school" (a type of vocational program) in 1834 and named Dr. Means its first rector. He was instrumental in the founding of Emory College (later, Emory University). When Emory College opened in 1836, he was chosen as the first chair of its physics department. He would later serve as president of the college between 1854 and 1855.

Dr. Means held simultaneous professorships at Emory College, Augusta Medical College, and Atlanta Medical School where he taught physics and chemistry. During the 1859-60 term, he delivered a twenty-six part lecture series on "A Nebular Theory of Planetary Formation."

Alexander Means was a man of exceptional diversity even in an age when diversity was the norm. He was a school teacher, college professor, pioneer of scientific education, medical doctor, scientist, statesman, college president, and poet.

Dr. Means became a Methodist minister in 1828 and was described as a "preacher of rare eloquence." He received speaking invitations from Dr. Wilbur Fisk, the president of Connecticut University, and President Zachary Taylor. Many of his sermons, speeches, reviews and scientific discussions were published and widely circulated.

The Methodist/Episcopal Georgia Conference formed a "manual labor school" (a type of vocational program) in 1834 and named Dr. Means its first rector. He was instrumental in the founding of Emory College (later, Emory University). When Emory College opened in 1836, he was chosen as the first chair of its physics department. He would later serve as president of the college between 1854 and 1855.

Dr. Means held simultaneous professorships at Emory College, Augusta Medical College, and Atlanta Medical School where he taught physics and chemistry. During the 1859-60 term, he delivered a twenty-six part lecture series on "A Nebular Theory of Planetary Formation."

Alexander Means was a man of exceptional diversity even in an age when diversity was the norm. He was a school teacher, college professor, pioneer of scientific education, medical doctor, scientist, statesman, college president, and poet.

Who Haunts Orna Villa?

Alexander Means was married to Sarah Ann Elizabeth and they had nine sons. The youngest, Toby, whose portrait is on the right, was a rebellious iconoclast and many believe it is he who haunts the house. However, some believe that the haunting is done by Toby's older brother, Dr. Olin Means.

Toby wanted nothing to do with his father's plans for him. He had no interest in the study of arts and sciences, or even in extensive reading. He told his father that he did not want to go to college, but rather wanted to get his education by traveling the world. He proposed that the money his father would have spent on college be given to him to pay for his travels. An argument ensued and Toby left the house that night, never to return. In the months and years that followed, family members are said to have heard footsteps, pacing on the back porch. Thinking it was Toby returning home, they would go to the door, but no one was there.

While Toby was the philosophical antithesis of his father, Olin was his shadow in every way but one: where the elder Means was a man of eclectic interests, the son was completely focused from an early age on medicine. Upon graduation from medical school, Olin set up practice close to the family home. Later in life, he felt the calling to go into preaching. It is said to have been a difficult decision for him, one that caused him to pace back and forth on the back porch of Orna Villa for days on end. He became ill and died before he reached a decision. It is for this reason that many believe that the phantom footsteps that haunt the home are those of Olin Means.

Toby wanted nothing to do with his father's plans for him. He had no interest in the study of arts and sciences, or even in extensive reading. He told his father that he did not want to go to college, but rather wanted to get his education by traveling the world. He proposed that the money his father would have spent on college be given to him to pay for his travels. An argument ensued and Toby left the house that night, never to return. In the months and years that followed, family members are said to have heard footsteps, pacing on the back porch. Thinking it was Toby returning home, they would go to the door, but no one was there.

While Toby was the philosophical antithesis of his father, Olin was his shadow in every way but one: where the elder Means was a man of eclectic interests, the son was completely focused from an early age on medicine. Upon graduation from medical school, Olin set up practice close to the family home. Later in life, he felt the calling to go into preaching. It is said to have been a difficult decision for him, one that caused him to pace back and forth on the back porch of Orna Villa for days on end. He became ill and died before he reached a decision. It is for this reason that many believe that the phantom footsteps that haunt the home are those of Olin Means.

The Ghost Stories of Orna Villa

The first extensive reports of haunting at Orna Villa began in 1945 when E.H. "Buddy" Rheberg and his wife bought the house.

Mrs. Rheberg's father, James Boykin Robinson, was Toby Means's closest childhood friend. It is said that Toby spent his last night in Oxford with Robinson. Several of the owners and visitors to the house have reported seeing -- but mostly hearing -- the ghost that haunts Orna Villa.

Here are a few of the documented stories:

Buddy Rheberg got up early one morning for breakfast and while he was preparing it, he heard footsteps on the gravel driveway. He was expecting his handyman, Walt, and so waited to hear Walt’s knock on the back door. He heard the footsteps climb the stairs and he called for Walt to come in, but rather than the door opening, the footsteps paced back and forth across the porch. Buddy shouted again for Walt to come in and, annoyed that Walt was ignoring him, went to the back door. He could still hear the footsteps as he put his hand on the doorknob, but as soon as he opened the door, the footsteps stopped and there was no one there. Walt arrived a half an hour later.

Mrs. Rheberg's father, James Boykin Robinson, was Toby Means's closest childhood friend. It is said that Toby spent his last night in Oxford with Robinson. Several of the owners and visitors to the house have reported seeing -- but mostly hearing -- the ghost that haunts Orna Villa.

Here are a few of the documented stories:

Buddy Rheberg got up early one morning for breakfast and while he was preparing it, he heard footsteps on the gravel driveway. He was expecting his handyman, Walt, and so waited to hear Walt’s knock on the back door. He heard the footsteps climb the stairs and he called for Walt to come in, but rather than the door opening, the footsteps paced back and forth across the porch. Buddy shouted again for Walt to come in and, annoyed that Walt was ignoring him, went to the back door. He could still hear the footsteps as he put his hand on the doorknob, but as soon as he opened the door, the footsteps stopped and there was no one there. Walt arrived a half an hour later.

Another story concerns the Rheberg's daughter, Betty. She came home after a date one night, locked the front door and went upstairs. Before going to her room, she cracked the door to her parent's room across the landing and whispered, "Mom, I'm home." Betty's father answered, "Your mom's asleep. Are you okay?" "Yes, I'm fine," Betty replied, and closed the door. Betty went to her room, turned her radio on low, and slipped into bed. She was just about to turn off her radio when she heard footsteps running up the stairs. Her door suddenly flung open and she screamed. Her father rushed out of his room and went to see what was the matter. No one was there.

Then there is the story about when the Rhebergs had the kitchen floor painted and closed the doors into the kitchen while it was drying. When they opened the door, there was a man's footprint in the paint even though no one had been in the room and the doors were locked.

Mr. Rheberg claimed that once the piano, which has reportedly been with the house since Alexander Means owned it, started playing all by itself. He has also claimed that windows and doors would often rattle violently as if someone -- or something -- was shaking them.

Mr. Rheberg claimed that once the piano, which has reportedly been with the house since Alexander Means owned it, started playing all by itself. He has also claimed that windows and doors would often rattle violently as if someone -- or something -- was shaking them.

Another story comes from another owner of Orna Villa, Jim Watterson. He had Civil War muskets mounted on the wall of one of the rooms, with an antique glass showcase underneath. One day, there was a terrible crash and he rushed in to find that all the muskets had fallen off the wall and onto the showcase. Mr. Watterson said that the brackets looked as though they had been yanked out of the wall; however, nothing was broken and the antique glass showcase didn't have a scratch on it.

Another time, Mr. Watterson said that in the same room, six valuable lithographs hanging on the wall all fell off the wall at the same time -- although all the hooks remained in the wall intact. None of the picture frames or the glass in the frames were broken or damaged in any way.

Glynora Watterson, Jim’s wife, had a canary that she especially loved. They were going on a trip for two days and left the bird with enough food and water to last during their absence. While they were away, Glynora had a premonition that she would never see her canary again. When they returned, the birdcage -- that hung securely on a deep hook -- was lying broken on the floor, even though there was no damage to the hook or to the birdcage where it was attached. The cage had to have been lifted from the hook, the Wattersons claimed; it could not have slipped off. The canary was found dead in the aquarium.

The Wattersons sold Orna Villa to the Tanners in the 1970’s. Dr. Tanner's daughter used the first floor study off the front parlor as her bedroom. She reported that she heard knockings on the walls and saw the doorknobs to her room turn by themselves. The doctor's in-laws reported the same thing when they stayed in the room.

Glynora Watterson, Jim’s wife, had a canary that she especially loved. They were going on a trip for two days and left the bird with enough food and water to last during their absence. While they were away, Glynora had a premonition that she would never see her canary again. When they returned, the birdcage -- that hung securely on a deep hook -- was lying broken on the floor, even though there was no damage to the hook or to the birdcage where it was attached. The cage had to have been lifted from the hook, the Wattersons claimed; it could not have slipped off. The canary was found dead in the aquarium.

The Wattersons sold Orna Villa to the Tanners in the 1970’s. Dr. Tanner's daughter used the first floor study off the front parlor as her bedroom. She reported that she heard knockings on the walls and saw the doorknobs to her room turn by themselves. The doctor's in-laws reported the same thing when they stayed in the room.

The Tanners reported seeing a brilliant white light coming from the room that Dr. Means used to use as his laboratory (which was his son's Toby's room before Toby left the home) even though no one was in the room and no lamps were lit.

All Dr. Tanner's young children reported seeing a man in their rooms at different times. Late one night, his five-year-old son asked him, "Daddy, who is that man in my room playing with my toys?"

Dr. Tanner's wife saw a tall thin man walk past her bedroom door. Her children were asleep and her husband was in a different part of the house.

All Dr. Tanner's young children reported seeing a man in their rooms at different times. Late one night, his five-year-old son asked him, "Daddy, who is that man in my room playing with my toys?"

Dr. Tanner's wife saw a tall thin man walk past her bedroom door. Her children were asleep and her husband was in a different part of the house.

Then there is the story of the two Methodist ministers who were visiting the Tanners. They stayed overnight in the first floor study (then being used as a bedroom). They asked to be awakened at eight the next morning, but when the doctor and his wife came down in the morning at eight, the two visitors were already up and dressed and drinking coffee. They said that at precisely six in the morning, there was a loud pounding on their door that woke them up. They thought someone in the house had come to wake them, but no one was there. It was only then that they were told of the legendary ghost that haunted the house.

Dr. Tanner saw what he described as a lanky man dressed in a long coat with a ruffled shirt and a string tie lounging in the hall. He had reddish hair and sideburns and was only visible for a few seconds. Being a devoutly religious man, Dr. Tanner went from room to room praying that if the man he saw was his guardian angel, then he should show himself, and if he wasn't his guardian angel, then he should leave Orna Villa and never return. There were no more sightings - for seven years.

Dr. Tanner saw what he described as a lanky man dressed in a long coat with a ruffled shirt and a string tie lounging in the hall. He had reddish hair and sideburns and was only visible for a few seconds. Being a devoutly religious man, Dr. Tanner went from room to room praying that if the man he saw was his guardian angel, then he should show himself, and if he wasn't his guardian angel, then he should leave Orna Villa and never return. There were no more sightings - for seven years.

As the present resident of Orna Villa, I must add that, all the ghost stories notwithstanding, I have never felt safer or more at home than I have at Orna Villa. I have gotten up in the middle of the night and walked through the house in the pitch dark without a twinge of fear or foreboding. Although a few oddities have occurred while I have lived here, they were not violent or in any way frightening. I only hope this means that our ghost is happy that I’m here (or at least, doesn’t mind).

A New Era for Orna Villa ... and Me

The week I moved into Orna Villa, there had been an uncharacteristically heavy snowfall. When I turned into the long driveway, everything seemed like a winter wonderland. Was it my imagination, or did the house look happy to see me? In any case, I never felt happier than when I stepped between Orna Villa’s massive white columns with keys in hand.

While finding Orna Villa was the realization of a dream I had clung to for so many years, I never imagined that it was even possible to find a community such as Oxford. Fifth and sixth generation families welcomed me as one of their own. Now, I not only have the home I’ve searched for all my life, I have a hometown.

While finding Orna Villa was the realization of a dream I had clung to for so many years, I never imagined that it was even possible to find a community such as Oxford. Fifth and sixth generation families welcomed me as one of their own. Now, I not only have the home I’ve searched for all my life, I have a hometown.