Oxford Life in 1910

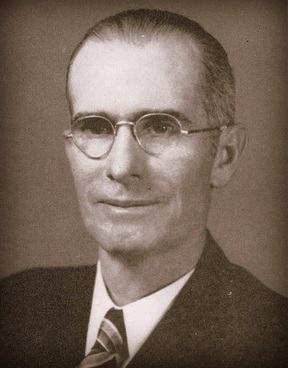

by Wilbur "Squire" Carlton

In 1910, when I arrived at Emory, Oxford was completely without pavement, plumbing in the homes, and electric lights, except for the Williams Gymnasium and Allen Memorial Church, which were furnished electricity by a dynamo in the boiler room of the gym. We obtained water from open wells for drinking as well as for all other purposes. However, the gym and the science buildings had their own water system. A hydraulic ram located in Dried Indian Creek pumped water into a tank at the gym and another near Pierce Hall. We had to do our studying by the light of a kerosene lamp. There were scarcely any automobiles and absolutely no co-eds at that particular time.

There was only one college dormitory, Marvin Hall, which was “outmoded’ even for 1910 and which could accommodate only a small part of the student body. It stood on almost the exact spot where a beautiful, modern home is now located in the large pecan grove facing south, near the Old Church. Most of the students lived in boarding houses (or private homes), of which there were several. And these were run by some of the world’s finest and most dedicated women, such as Miss Lynn Branham, Mrs. J.Z. Johnson, and Misses Emmie and Sallie Stewart, to name a few.

The college had 300 students. I had a room in one of three little cottages near the Old Church which had been dubbed “Angels’ Retreat” by someone with a keen sense of humor. Our meals in the dining hall cost us the staggering amount of $8.00 or $9.00 per month. Even so, at times we were constrained to think that we were not getting too much of a bargain. But “Uncle” Jess and “Aunt” Hannah continued to replenish our biscuit plates till we were filled, since we always had plenty of syrup or sorghum and country butter to go with the biscuits.

There was only one college dormitory, Marvin Hall, which was “outmoded’ even for 1910 and which could accommodate only a small part of the student body. It stood on almost the exact spot where a beautiful, modern home is now located in the large pecan grove facing south, near the Old Church. Most of the students lived in boarding houses (or private homes), of which there were several. And these were run by some of the world’s finest and most dedicated women, such as Miss Lynn Branham, Mrs. J.Z. Johnson, and Misses Emmie and Sallie Stewart, to name a few.

The college had 300 students. I had a room in one of three little cottages near the Old Church which had been dubbed “Angels’ Retreat” by someone with a keen sense of humor. Our meals in the dining hall cost us the staggering amount of $8.00 or $9.00 per month. Even so, at times we were constrained to think that we were not getting too much of a bargain. But “Uncle” Jess and “Aunt” Hannah continued to replenish our biscuit plates till we were filled, since we always had plenty of syrup or sorghum and country butter to go with the biscuits.

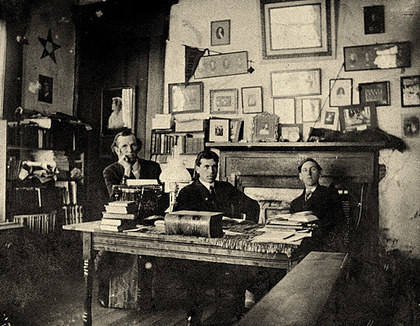

Our rooms were furnished in keeping with the over-all picture that has been painted, crudely and scantily: bed, dresser, table, two chairs, washstand, water bucket, dipper, basin and its necessary complement, an old papier mâché bucket into which we poured waste water. And of course it was convenient in case of emergency during the night. We took showers at the gym. There was a grate in which we had fire during cold weather, and a mantel over the fireplace.

In our junior year, we moved to living quarters in the Johnson House, where the Jarrells now live. Mrs. Johnson furnished us our meals also. And what meals! She was a sweet, motherly woman whom we all loved and respected very much. Our room and board came to $20.00 a month, I think. But at no price could such meals be had anywhere now, in my opinion. There were several students who didn’t room there that took their meals with Mrs. Johnson, too, and also one elderly man, Judge Capers Dickson, who was a great raconteur. Our living room was a sort of rendezvous for many of those who lived elsewhere. We had two or three decks of Rook cards, and on Saturday nights we generally had guests enjoying our hospitality.

We had to furnish our own coal. Our coal pile was out in the back yard a fairly good distance from the house. It was disagreeable to have to go out for a scuttle of coal during rough weather, especially at night. Since it was a little trouble to remember whose turn it was to go for the coal, we resorted to “matching” in order to decide. We each carried a penny. Whenever the coal got too low and the fire began cooling off, one of us would say, “Get out your penny,” and we’d match. The odd man dropped out, and the remaining two matched again. The loser went for the coal.

During the summer of 1912, one of our classmates, M. M. Marshall, who was married and quite a business man, had arranged with the towns of Covington and Oxford to extend the power line from Covington into Oxford. So we were the first class to graduate from Emory “under” electric lights.

One can well imagine that because of the absence of plumbing we were confronted with problems with which present-day students do not have to cope. To take care of this situation, each home had what we shall euphemistically call its own private “comfort station” to which one could resort whenever Nature called. We had such a station on the campus, commonly referred to as the “Gym-Bank,” situated behind the gym in the woods. It was patronized mainly in case of emergency. This important and indispensable institution was situated well to the rear, isolated as much as possible by trees or shrubbery. Of course it was rather inconvenient to answer a summons in the “wee small” hours of the night when it was cold, perhaps with snow on the ground. But we got along quite all right and were happy. I can’t believe that any students anywhere at any time could be more pleasantly accommodated. We were living in an earthly paradise and knew it not.

An occasion of much interest in the old days was the Newton County Oratorical Contest, in which all the public schools in the county were represented. This was before the day of the consolidated school, or course. This was held in the Old Church, and appropriate recognition was awarded the winners. It was a great day. Wagons drawn by horses, mules, and oxen conveyed the contestants and visitors to the scene. A big tent was stretched in front of the Old Church right in the road. Dinner was served on the ground, and the food was assembled in the tent as it was brought in.

In our junior year, we moved to living quarters in the Johnson House, where the Jarrells now live. Mrs. Johnson furnished us our meals also. And what meals! She was a sweet, motherly woman whom we all loved and respected very much. Our room and board came to $20.00 a month, I think. But at no price could such meals be had anywhere now, in my opinion. There were several students who didn’t room there that took their meals with Mrs. Johnson, too, and also one elderly man, Judge Capers Dickson, who was a great raconteur. Our living room was a sort of rendezvous for many of those who lived elsewhere. We had two or three decks of Rook cards, and on Saturday nights we generally had guests enjoying our hospitality.

We had to furnish our own coal. Our coal pile was out in the back yard a fairly good distance from the house. It was disagreeable to have to go out for a scuttle of coal during rough weather, especially at night. Since it was a little trouble to remember whose turn it was to go for the coal, we resorted to “matching” in order to decide. We each carried a penny. Whenever the coal got too low and the fire began cooling off, one of us would say, “Get out your penny,” and we’d match. The odd man dropped out, and the remaining two matched again. The loser went for the coal.

During the summer of 1912, one of our classmates, M. M. Marshall, who was married and quite a business man, had arranged with the towns of Covington and Oxford to extend the power line from Covington into Oxford. So we were the first class to graduate from Emory “under” electric lights.

One can well imagine that because of the absence of plumbing we were confronted with problems with which present-day students do not have to cope. To take care of this situation, each home had what we shall euphemistically call its own private “comfort station” to which one could resort whenever Nature called. We had such a station on the campus, commonly referred to as the “Gym-Bank,” situated behind the gym in the woods. It was patronized mainly in case of emergency. This important and indispensable institution was situated well to the rear, isolated as much as possible by trees or shrubbery. Of course it was rather inconvenient to answer a summons in the “wee small” hours of the night when it was cold, perhaps with snow on the ground. But we got along quite all right and were happy. I can’t believe that any students anywhere at any time could be more pleasantly accommodated. We were living in an earthly paradise and knew it not.

An occasion of much interest in the old days was the Newton County Oratorical Contest, in which all the public schools in the county were represented. This was before the day of the consolidated school, or course. This was held in the Old Church, and appropriate recognition was awarded the winners. It was a great day. Wagons drawn by horses, mules, and oxen conveyed the contestants and visitors to the scene. A big tent was stretched in front of the Old Church right in the road. Dinner was served on the ground, and the food was assembled in the tent as it was brought in.

There were three or four places where the students did most of their “hanging out.” Bill Burt’s Arcade was the number one spot. It was situated northwest of the town hall, just across the street, where the asbestos-siding dwelling of Mr. Day now stands. If you asked Bill for an item that he did not have in stock, he would say, “I’m sorry, I haven’t got it; but I’ll order it for you.” He used to say that he would order anything from a horseshoe nail to an automobile. He carried text books, lab supplies, athletic equipment, etc. He had a soda fountain and carried all kinds of candies, pennants, college jewelry, and sofa pillows with “Emory” or “E” imprinted on them.

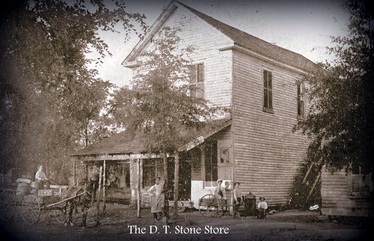

Stone’s Store was the number two spot, or maybe Frank Henderson’s Store was number two and Stone’s number three. Be that as it may, these were two of the main hangouts. It was in Henderson’s Store that I first saw shelled peanuts put into bottles of Coca-Cola. And that’s where we used to have oyster suppers on Saturday nights in oyster season.

Where We Gathered

Mr. D.T. Stone was one of the most unique characters I’ve ever known. He was uneducated from an academic standpoint. The “Queen’s English” took a beating from him, and some called him “Fotch-it” Stone. But he was a philosopher with a keen sense of humor, a man’s man who was equally at ease in the presence of a college president, a U.S. Senator, and a janitor. It was a customary sight to see President Dickey or one of the professors sitting on an old, rough wooden bench in front of the store talking to Mr. Stone. Perhaps they would be playing checkers or chess. The outstanding contribution that his store made, aside from the social aspect, was the delicious chocolate milks covered with real whipped cream that Henry (Heine) Stone served at the soda fount. Mr. Stone had the reputation of being lucky. Stone’s Store stood a short distance north of the Leland Ellis home, fronting right on the sidewalk.

There was one more place where students gathered that will have to be mentioned to paint anything like an adequate picture of the Oxford of 1910. That was the barber shop. It was located across a narrow driveway just south of Stone’s store in a rather antiquated frame building of two stories. Really, I guess you could say it was in the Town Hall since the town council met in an adjoining room. Jim (Barber) Rawlins was the proprietor and sole operator of this enterprise. His prices were in keeping with those of the times: head scratch 10 cents, shave 15 cents, haircut 25 cents, and massage 25 cents. “Barber” was popular with the students and entered into their activities as an enthusiastic fan, even acting as water boy at football games. His yells and laughter rang out above the confusion and noise of “battle.” He lived in the house under the big oak [Yarbrough Oak] near the Post Office and rented a room to students. There was a checker board within easy range generally both at the barber shop and the home. And there was nearly always a game in progress. Rook was another game that enjoyed great popularity about that time. In my mind’s eye I can see students sitting out on the porch during mild days playing Rook. The Barber Shop was one of the main “clearing houses” for jokes and the latest news. And “Barber” was a much beloved individual.

The Oxford we enjoyed has, out of necessity, changed with the changing world. Two world wars, the industrial and social revolutions, and the removal of Emory College to Atlanta have contributed toward the bringing about of many changes. That old Oxford, even without the modern conveniences we now enjoy, was the nearest approach to Utopia I ever expect to see.

There was one more place where students gathered that will have to be mentioned to paint anything like an adequate picture of the Oxford of 1910. That was the barber shop. It was located across a narrow driveway just south of Stone’s store in a rather antiquated frame building of two stories. Really, I guess you could say it was in the Town Hall since the town council met in an adjoining room. Jim (Barber) Rawlins was the proprietor and sole operator of this enterprise. His prices were in keeping with those of the times: head scratch 10 cents, shave 15 cents, haircut 25 cents, and massage 25 cents. “Barber” was popular with the students and entered into their activities as an enthusiastic fan, even acting as water boy at football games. His yells and laughter rang out above the confusion and noise of “battle.” He lived in the house under the big oak [Yarbrough Oak] near the Post Office and rented a room to students. There was a checker board within easy range generally both at the barber shop and the home. And there was nearly always a game in progress. Rook was another game that enjoyed great popularity about that time. In my mind’s eye I can see students sitting out on the porch during mild days playing Rook. The Barber Shop was one of the main “clearing houses” for jokes and the latest news. And “Barber” was a much beloved individual.

The Oxford we enjoyed has, out of necessity, changed with the changing world. Two world wars, the industrial and social revolutions, and the removal of Emory College to Atlanta have contributed toward the bringing about of many changes. That old Oxford, even without the modern conveniences we now enjoy, was the nearest approach to Utopia I ever expect to see.

African American Helpers

No account of my old school days at Emory would be complete without mentioning some of our [African American] friends who contributed in a material way to our pleasures as well as our necessities. As we were being driven through the campus on that first day in Oxford, “Old Bass” was standing in the door of the Chapel.

We didn’t have many janitors at that time. I should use the work caretakers, for they took pride in their work. Only two others of the old helpers on the campus still remain in my memory, “Uncle Bob” Hammond and “Billy” Mitchell. They were two great characters. I’ve heard it said that Uncle Bob made a liberal contribution to the Emory Endowment Fund during the drive of 1909-10. He was a quiet, cheerful, industrious, and efficient worker. He was as honest and reliable as a person can be.

The same can be said for Billy. Billy’s chief concern was the new J. P. Williams Gymnasium, at that time just about the best in this part of the world. No one was allowed on that maple floor without rubber-soled shoes. Billy had charge of the boiler room, and dynamo. There was a heating system for the gym, but all classrooms used stoves. Billy was responsible for the heating, cleaning, and general upkeep of the gym. And he had a little private enterprise in a cubbyhole, where he rented towels to students who had failed to furnish themselves before coming to gym. He was also our “masseur” and was responsible for our equipment when we had a track meet. He always went along. A few months ago I had a little white oak planted in front of Few Hall in honor of Billy, who for over fifty years had trod those walks and with loving hands had cared for the campus.

We didn’t have many janitors at that time. I should use the work caretakers, for they took pride in their work. Only two others of the old helpers on the campus still remain in my memory, “Uncle Bob” Hammond and “Billy” Mitchell. They were two great characters. I’ve heard it said that Uncle Bob made a liberal contribution to the Emory Endowment Fund during the drive of 1909-10. He was a quiet, cheerful, industrious, and efficient worker. He was as honest and reliable as a person can be.

The same can be said for Billy. Billy’s chief concern was the new J. P. Williams Gymnasium, at that time just about the best in this part of the world. No one was allowed on that maple floor without rubber-soled shoes. Billy had charge of the boiler room, and dynamo. There was a heating system for the gym, but all classrooms used stoves. Billy was responsible for the heating, cleaning, and general upkeep of the gym. And he had a little private enterprise in a cubbyhole, where he rented towels to students who had failed to furnish themselves before coming to gym. He was also our “masseur” and was responsible for our equipment when we had a track meet. He always went along. A few months ago I had a little white oak planted in front of Few Hall in honor of Billy, who for over fifty years had trod those walks and with loving hands had cared for the campus.

“Uncle” Jess and “Aunt” Hannah Cureton were our cooks at Marvin Hall. Then there was Zach Perry, Bishop Candler’s old butler, who took us boys possum hunting; and “Aunt” Nuncie Thomas who could launder shirts as well as a commercial laundry; “Aunt Sally,” our cook at Mrs. Johnson’s; Jim Middlebrooks, who served as butler and waiter for Mrs. Johnson.

Henry (Plink) Simms really deserves special attention and consideration. He worked for Bill Burt (owner of the Arcade), mainly in his Pressing Club. And that was no ordinary pressing club. Every morning “Plink” came around and collected the clothes to be pressed and brought them back in the afternoon. This service cost us $1.00 per month, and we could send a suit every week day. Plink was quite a character. He was a stutterer and had about the hardest time getting his jaws “unlocked” of any person I’ve ever seen.

Then there was the large number of the women who laundered our clothes at the price of 25 cents per week and never complained about the size of the wash. And at Miss Emmie’s was Richard Gaither, waiter, butler, and general factotum par excellence. No doubt Richard is known by more Emory students than any of our previously mentioned friends. Both campuses are familiar grounds to him.

These who have been named are only a small part of those worthy of being included.

Henry (Plink) Simms really deserves special attention and consideration. He worked for Bill Burt (owner of the Arcade), mainly in his Pressing Club. And that was no ordinary pressing club. Every morning “Plink” came around and collected the clothes to be pressed and brought them back in the afternoon. This service cost us $1.00 per month, and we could send a suit every week day. Plink was quite a character. He was a stutterer and had about the hardest time getting his jaws “unlocked” of any person I’ve ever seen.

Then there was the large number of the women who laundered our clothes at the price of 25 cents per week and never complained about the size of the wash. And at Miss Emmie’s was Richard Gaither, waiter, butler, and general factotum par excellence. No doubt Richard is known by more Emory students than any of our previously mentioned friends. Both campuses are familiar grounds to him.

These who have been named are only a small part of those worthy of being included.